Everything You Wanted to Know About Severely Whipping and "Beating" Your Sex Partner

On March 23, 2013, members of Alif Laam Meem, a national Muslim fraternity based at the University of Texas at Dallas, stood up against domestic violence equally Muslims and as men of Dallas.

The human relationship between Islam and domestic violence is disputed. Even among Muslims, the uses and interpretations of Sharia, the moral code and religious law of Islam, lack consensus. Variations in estimation are due to different schools of Islamic jurisprudence, histories and politics of religious institutions, conversions, reforms, and education.[one]

Domestic violence amid the Muslim community is considered a complicated homo rights issue due to varying legal remedies for women by the nations where they live, the extent to which they accept back up or opportunities to divorce their husbands, cultural stigma to hide evidence of corruption, and inability to have abuse recognized past police or the judicial arrangement in some Muslim nations.

Definition

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary definition, domestic violence is: "the inflicting of physical injury past 1 family or household member on some other; also: a repeated or habitual blueprint of such beliefs."[2]

Coomaraswamy defines domestic violence as "violence that occurs within the individual sphere, generally between individuals who are related through intimacy, blood or constabulary…[It is] nearly always a gender-specific law-breaking, perpetrated by men against women." It used is equally a potent form of command and oppression.[3]

In 1993, The United nations Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women divers domestic violence as:

Physical, sexual and psychological violence occurring in the family, including battering, sexual abuse of female children in the household, dowry-related violence, marital rape, female person genital mutilation and other traditional practices harmful to women, non-spousal violence and violence related to exploitation.[four]

Islamic texts

In the Quran

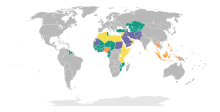

Employ, by state, of Sharia for legal matters relating to women:

Sharia plays no role in the judicial organization

Sharia applies in personal status issues

Sharia applies in total, including criminal police

Regional variations in the application of sharia

The interpretation of Surah An-Nisa, 34 is subject to debate amidst Muslim scholars, forth with the various translations of the passage which can read 'strike them' or '(lightly) strike them' or 'beat them' or 'scourge them' or 'accept practical action with them',[5] depending on the translator.[6] Quran 4:34 reads:

Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because Allah has given the one more (strength) than the other, and because they back up them from their means. Therefore the righteous women are devoutly obedient, and baby-sit in (the hubby's) absence what Allah would have them guard. As to those women on whose office ye fear disloyalty and sick-conduct, admonish them (first), (Side by side), pass up to share their beds, (And last) strike them (lightly); but if they return to obedience, seek non confronting them Means (of badgerer): For Allah is Nearly High, great (above y'all all).

Quran interpretations that support domestic violence

Hajjar Lisa[7] [eight] claims Shari'a law encourages "domestic violence" against women when a husband suspects nushuz (disobedience, disloyalty, rebellion, sick deport) in his wife.[9] Other scholars claim wife beating, for nashizah, is non consistent with mod perspectives of Qur'an.[10] Some conservative translations observe that Muslim husbands are permitted to human activity what is known in Arabic as Idribuhunna with the use of "Strike," and sometimes as much as to hit, chastise, or beat out.[11]

In some exegesis such as those of Ibn Kathir(1300-1373AD) and Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari(839-923AD), the deportment prescribed in Surah 4:34 in a higher place, are to be taken in sequence: the husband is to admonish the wife, later which (if his previous correction was unsuccessful) he may remain dissever from her, later on which (if his previous correction was still unsuccessful) he may[12] [13] [nb i] [nb two] give her a low-cal tapping with a Siwak.[16] Ibn 'Abbas, The Cousin of the Prophet, is recorded in the Tafsir of al-Tabari for verse 4:34 every bit proverb that beating without severity is using a siwak (small toothbrush) or a similar object.[17]

A translated passage by Taqi-ud-Din al-Hilali and Muhsin Khan in 2007 defines men as the protectors, guardians and maintainers of women, because Allah has made the one of them to excel the other, and because they spend (to back up them) from their means. Upon seeing ill-acquit (i.e. defiance, rebellion, nashuz in Arabic) past his wife, a man may admonish them (starting time), (side by side), reject to share their beds, (and last) beat them (lightly, if it is useful), only if they render to obedience, seek not confronting them ways.[18]

Some Islamic scholars and commentators have emphasized that hit, even where permitted, is not to be harsh[12] [19] [nb iii] or some even argue that they should be "more than or less symbolic."[21] [nb 4] According to Abdullah Yusuf Ali and Ibn Kathir, the consensus of Islamic scholars is that the above poetry describes a light chirapsia.[14] [23] Abu Shaqqa refers to the edict of Hanafi scholar al-Jassas (d. 981) who notes that the reprimand should be "A not-violent accident with siwak [a small stick used to clean the teeth] or similar. This means that to hitting with any other means is legally Islamically forbidden."[24]

Quran interpretations that do not support domestic violence

Indicating the subjective nature of the translations, particularly regarding domestic abuse, Ahmed Ali's English translation of the give-and-take idribu is "to forsake, avert, or leave."[ commendation needed ] His English language translation of Quran 4:34 is: ...Every bit for women yous feel are averse, talk to them cursively; then get out them alone in bed (without molesting them), and go to bed with them (when they are willing).[25] However, in his native Urdu translation of verse 4:34, he translates idribuhunna as "strike them."[26]

Laleh Bakhtiar postulates that daraba is defined as "to become abroad."[27] This interpretation is supported past the fact that the word darabtum, which means to "go abroad" in the sake of Allah, is used in the same Surah (in 4:94) and is derived from the same root word (daraba) as idribuhunna in 4:34.[28] However, this translation is negated by the fact that virtually definitions of daraba in Edward William Lane's Standard arabic-English Dictionary are related to physical chirapsia[29] and that when the root word daraba and its derivatives are used in the Qur'an in relation to humans or their torso parts, it exclusively means physically hit them with a Siwak(Toothbrush) (eastward.g. in Qur'an 2:7337:93, eight:12, 8:50, 47:iv and 47:27).[ non-primary source needed ]

The keywords of Verse 34 of Surah An-Nisa come with various meanings, each of which enables united states of america to know a distinct aspect, meaning and thing. Each aspect, i.e., meanings proposed past commentators, translators, and scholars throughout history for this verse, is according to a distinct wonted system of the family in history. "Zarb" does not hateful attack or whatsoever form of violence against women. Rather, it means a practical activity to inspire ill-behaved women to obey the legitimate rights of their spouse.[xxx]

Jurisprudence

The discussions in all four Sunni law schools institutionalised the viewpoint of the Quranic exegeses by turning wife-beating into a ways of subject field against rebellious wives.[31] Ayesha Chaudhry has examined the pre-colonial Hanafi texts on domestic violence.[31] Her findings are equally follows. Hanafi scholars emphasised the procedure of admonishing, abandoning and hit the wife. The Hanafi jurists say that it is the husband's duty to physically discipline his wife'due south airs (nushuz). They permitted the husband a lot of leeway in the severity of the beating. While Hanafi scholars admonish husbands to treat their wives with kindness and equity, they do not recognize the principle of qisas (retributive punishment) for injuries sustained in marriage, unless they crusade death, permitting the hubby to hit his wife without any liability and that Hanafi scholars affirm that the husband is allowed to hit his wife even if that causes wounds or cleaved basic their only status is that the chirapsia must not kill her this view was taken from Hanafi Scholar Al-Jassas and within this framework they emphasised the need of post-obit the sequence of admonishment, abandonment and hit.[32] Yet, al-Jassas also says that the reprimand should merely be "A non-vehement accident with siwak [a small stick used to clean the teeth] or something similar to it.[24]

Al-Kasani added that the admonishment contains two steps: gentle admonishment and so harsh admonishment. [33] Al-Nasafi adds that if a married woman dies during sex, the husband is not liable, Al-Nasafi interpreted this to be the position of Imam Abu Hanifah.[34] Ḥanafi Scholars used general qualifiers to describe the type of hitting a husband might undertake when disciplining his wife the hitting should be non-extreme (ghayr mubarrih) and that should not crusade disfigurement.[34] Ibn al-Humam believed that a husband can whip his married woman with only ten lashes.[34] Even so, al-Nasafi put the maximum limit at 100 lashes.[35] Al-Nasafi besides ruled that if a married woman dies from the beating the married man is not liable as long as he does not exceed 100 strikes. However, if he exceeds 100 lashes and then he is considered to have crossed the limit of discipline into corruption and he would have to pay blood money (diya).[36] Ibn Nujaym and al-Haskafi likewise ruled that a husband cannot be punished with the expiry penalty if he kills his married woman while disciplining her. He only owes blood money.[37]

Evidence of judicial records from the sixteenth century on wards prove that Ottoman judges who followed the Hanafi schoolhouse allowed divorce because of corruption. This did this partially by borrowing rulings from other schools of thought and partially past blending corruption with blasphemy since they reasoned a "truthful Muslim would not beat out his married woman."[38] [37] A number of women in British India between the years of 1920 and 1930s left Islam to obtain judicial divorce considering Hanafi constabulary did not permit women to seek divorce in instance of vicious treatment by a married man. Mawlana Thanawi reviewed the event and borrowed the Maliki rulings which permits women to seek divorce because of cruelty by the married man. He expanded the grounds of divorce available to women under Hanafi law.[39]

According to Ayesha Chaudhary, dissimilar Hanafi scholars who were more interested in protecting a husband's right to hit his wife for disciplinary purposes, the Malikis tried to stop husbands from abusing this right.[31] The Maliki scholars only allowed striking a rebellious wife with the purpose of rectifying her. They specified that the strike should non exist extreme or severe, must non get out marks or cause injuries and that the strike must not be fearsome, cause fractures, break bones, cause disfiguring wounds while punching in general and punching her in the chest were unacceptable and that the strike could not harm the wife. The Malikis held that a married man would be legally liable if the striking led to the wife's death. They also did not allow a husband to striking his wife if he did not believe the hitting would cause her to cease her arrogance.[forty] The Shafi'i scholars upheld the permissibility of wife beating but encouraged fugitive it and did not agree the imperative "wa-ḍribūhunna" to hateful an obligatory command. Shafi scholars also restricted what the husband could exercise in regards to hitting his wife, that he should just hit his wife if he thinks it will be effective in deterring her from her airs ; he should hitting her in a non-extreme (ghayr mubarrih) manner; he should avert hitting her face, sensitive places, and places of beauty and not striking her in a mode that causes disfiguration, bleeding, that he should not striking the aforementioned place repeatedly, loss of limbs, or death. According to Shafi scholars a husband is permitted to hitting his wife with a cloth, sandal and a siwak but non with a whip.[40] The views of the Hanbali scholars are a mix of the positions of the other three schools of law.[31]

Undesirability of beating

Jonathan A.C. Brownish says:

The vast majority of the ulama beyond the Sunni schools of police inherited the Prophet's unease over domestic violence and placed farther restrictions on the evident pregnant of the 'Wife Chirapsia Verse'. A leading Meccan scholar from the second generation of Muslims, Ata' bin Abi Rabah, counseled a husband not to beat his wife even if she ignored him but rather to express his anger in another mode. Darimi, a teacher of both Tirmidhi and Muslim bin Hajjaj too every bit a leading early on scholar in Islamic republic of iran, collected all the Hadiths showing Muhammad's disapproval of beating in a chapter entitled 'The Prohibition on Hit Women'. A thirteenth-century scholar from Granada, Ibn Faras, notes that i camp of ulama had staked out a stance forbidding striking a married woman altogether, declaring it contrary to the Prophet's example and denying the actuality of whatever Hadiths that seemed to allow beating. Even Ibn Hajar, the pillar of late medieval Sunni Hadith scholarship, concludes that, contrary to what seems to be an explicit command in the Qur'an, the Hadiths of the Prophet exit no doubt that striking 1's wife to discipline her really falls under the Shariah ruling of 'strongly disliked' or 'disliked verging on prohibited'.[41]

According to Laurels, Violence, Women and Islam, and Islamic scholar Dr. Muhammad Sharif Chaudhry, Muhammad condemns violence against women, by saying: "How loathsome (Ajeeb) it is that one of you should hit his married woman as a slave is hit, and then sleep with her at the end of the mean solar day."[42] [43] [44]

Restraint in chirapsia

Percentage of women aged 15–49 who think that a husband/partner is justified in striking his wife/partner under certain circumstances, in some Arab and Muslim majority countries, according to UNICEF (2013)[45]

Scholars and commentators have stated that Muhammad directed men not to hitting their wives' faces,[46] not to beat their wives in such a way equally would exit marks on their body,[46] [nb five] and not to shell their wives as to cause pain (ghayr mubarrih).[21] Scholars too have stipulated confronting beating or disfigurement, with others such as the Syrian jurist Ibn Abidin prescribing ta'zir punishments against calumniating husbands.[47]

In a certain hadith, Muhammad discouraged beating ane'southward wife severely:

Bahz bin Hakim reported on the authorization of his father from his grandfather (Mu'awiyah ibn Haydah) as saying: "I said: Messenger of Allah, how should we approach our wives and how should we exit them? He replied: Approach your tilth when or how you lot will, give her (your married woman) food when yous take nutrient, clothe when you lot clothe yourself, do not revile her face, and do non beat her."[48] [49] The same hadith has been narrated with slightly dissimilar wording.[50] In other versions of this hadith, just beating the face is discouraged.[51] [52]

Some jurists argue that even when beating is acceptable under the Quran, it is still discouraged.[nb vi] [nb 7] [nb 8] Ibn Kathir in concluding his exegesis exhorts men to not beat their wives, quoting a hadith from Muhammad: "Practise not hitting God's servants" (here referring to women). The narration continues, stating that some while later on the edict, "Umar complained to the Messenger of God that many women turned against their husbands. Muhammad gave his permission that the men could hit their wives in cases of rebelliousness. The women then turned to the wives of the Prophet and complained near their husbands. The Prophet said: 'Many women have turned to my family unit lament nigh their husbands. Verily, these men are not among the best of you."[53]

Incidence amongst Muslims

Domestic violence is considered to be a problem in Muslim-majority cultures, where women confront social pressures to submit to vehement husbands and not file charges or flee.[54]

In deference to Surah 4:34, many nations with Shari'a law have refused to consider or prosecute cases of "domestic abuse."[55] [56] [57] [58] In 2010, the highest courtroom of United Arab Emirates (Federal Supreme Courtroom) considered a lower court's ruling, and upheld a hubby'due south correct to "chastise" his married woman and children physically. Article 53 of the United Arab Emirates' penal code acknowledges the right of a "chastisement by a husband to his wife and the chastisement of modest children" so long equally the assault does not exceed the limits prescribed by Shari'a.[59] The Council of Islamic Ideology, a ramble body of Pakistan that advises the government on the compatibility of laws with Islam, has recommended authorizing husbands to 'lightly' shell disobedient wives.[threescore] When asked why is beating a wife lightly permitted? The chairman of Pakistan's Quango of Islamic Ideology, Mullah Maulana Sheerani said, "The recommendations are according to the Quran and Sunnah. You can not ask someone to reconsider the Quran".[61] In Lebanon, KAFA, an organisation candidature confronting violence and the exploitation of women, alleges that as many as three-quarters of all Lebanese females accept suffered physically at the hands of husbands or male relatives at some indicate in their lives. An try has been underway to remove domestic violence cases from Shari'a driven religious courts to ceremonious penal lawmaking driven courts.[62] [63] Social workers claim failure of religious courts in addressing numerous instances of domestic corruption in Syria, Islamic republic of pakistan, Egypt, Palestine, Morocco, Iran, Yemen and Saudi Arabia.[64] In 2013 Saudi arabia approved a new law on domestic violence, which sets penalties for all types of sexual and physical abuse, in the workplace and at dwelling house. Penalties tin can be upward to a year in prison house and a fine up to 13,000 dollars. The law also provides shelter for the victims of domestic violence.[65]

Co-ordinate to Pamela One thousand. Taylor, co-founder of Muslims for Progressive Values, such violence is non office of the religion, but rather more than of a cultural aspect.[66] In the academic publication Honour, Violence, Women and Islam edited by Mohammad Mazher Idriss and Tahir Abbas, it is said that there is no authority in the Quran for the type of regular and frequent acts of violence that women feel from their abusive husbands. Furthermore, the actions of many Muslim husbands lack the expected level of command in two elements from the verse, admonishment and separation.[43] The separation dictates not only the physical separation, but also abstinence from marital sex.

| Nation | Information on Incidence |

|---|---|

| Transitional islamic state of afghanistan | Co-ordinate to HRW 2013 report, Afghanistan has ane of the highest incidence rates of domestic violence in the world. Domestic violence is so mutual that 85 per cent of women admit to experiencing it. lx% of all women report being victims of multiple forms of serial violence.[67] Afghanistan is the merely country in which the female suicide rate (at fourscore%) is higher than that of males.[68] Psychologists attribute this to an endless cycle of domestic violence and poverty.[69] |

| Bangladesh | According to a WHO, Un study, thirty% of women in rural Bangladesh reported their commencement sexual experience to be forced.[lxx] About 40% report having experienced domestic violence from their intimate partner, and fifty% in rural regions study experiencing sexual violence.[71] Statistics from four United Nations studies, from 1990s, show that 16-xix% of the women (age less than 50) were victims of domestic abuse within the previous 12-month menstruum. twoscore-47% of the women had been subject to domestic violence during some period of their life. The studies were performed in villages (1992, 1993), Dhaka (2002) and Matlab (2002).[72] About ninety% of women in Bangladesh are practicing Muslims, which indicates that many Muslim women are victims of concrete domestic violence in this country.[73] From a World Wellness System (WHO) study, of which People's republic of bangladesh was 1 of 10 participating countries, it was found that less than 2% of domestic abuse victims seek back up from the community to resolve calumniating situations, primarily considering they know that they won't receive the back up they need to remedy the issue.[74] Naved and Perrson write in their article "Factors Associated with Physical Spousal Corruption of Women During Pregnancy in People's republic of bangladesh" that women who are pregnant are more than probable to be abused. A report on Islamic republic of pakistan Rural Access and Mobility Written report (PRAMS) data showed that 67% of perpetrators were husbands or partners".[75] Bangladesh was found to be ane of the countries with a loftier rate of domestic violence resulting in death during pregnancy past a Un study.[72] [nb 9] |

| Arab republic of egypt | A 2012 United nations Women's report plant that 33% of women in Egypt have experienced physical domestic violence in their lifetime, while 18% study having experienced domestic physical violence in terminal 12 months.[76] Another Un national written report in 1995, 13% of the women (age 15-49) were victims of domestic abuse within the previous 12-month period. 34% of the women had been subject to domestic violence during some menstruation of their life. In a 2004 report of meaning women in El-Sheik Zayed 11% of the women (historic period 15-49) studied were victims of domestic abuse within the previous 12-month period and, also, during some menses of their life.[72] According to Egyptian Centre for Women's Rights and World Bank Social Development Group's 2010 report, 85% of Egyptian women report of having experienced sexual harassment.[77] |

| Republic of india | Muslim women in medieval Republic of india were subservient. They were devoted to their husbands and would bear the concrete and psychological violence inflicted on them by their husbands or in-laws. Sultan Nasir-ud-din refused to provide his wife with a servant after her fingers were burnt while baking breadstuff for him. She never expressed her complaint again. Mughis tortured his wife, the sister of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq, to death. During the rule of Sikandar Lodi a husband was reported to have used force on his wife after he falsely accused her of stealing a jewel. Khwaja Muazzam was known for his mistreatment of his wife whom he eventually murdered.[78] In one account narrated past Tavernier a physician in one case threw his wife off a roof. She sustained broken ribs only survived. On the second occasion, the physician stabbed his wife and children to death but the governor whom the physician was working nether did not take any activity.[79] A collection of legal documents and contracts from the time of Akbar, called Munshat i Namakin, reveal that Muslim brides would often make four stipulations in their marriage contracts. If the husband violated these conditions, the wife would exist entitled to divorce. These were conditions such as the husband would not marry a 2nd wife or take a concubine. Some other condition was that the husband would not shell the wife in a fashion which would go out a marker on her body, unless she was guilty of a serious offence. A miniature from the time of Akbar'southward reign shows a husband lashing his wife on the buttocks with a stick. This reflects the stipulation establish in marriage contracts of that time which were against beating in such a style that it would exit whatever mark on the body.[80] Ane 17th century Muslim wedlock contract from Surat, examined by Shireen Moosvi, contained a stipulation by the bride, Maryam, that her husband, Muhammad Jiu, would requite her a specific corporeality of maintenance. The amount of maintenance which was specified in it indicated that the couple belonged to the lower middle class. Nonetheless, the union contract contained no stipulation against wife-beating. This reflects that women of that socio-economic class were expected to submit to any kind of violence by their husbands.[81] |

| Republic of indonesia | The Globe Health Organization reported sharply increasing rates of domestic violence in Republic of indonesia, with over 25,000 cases in 2007. Most 3 in 4 cases, it is the husband chirapsia the wife; the side by side largest reported category were the in-laws abusing the wife. The higher rates may exist considering more cases of violence against women are beingness reported in Republic of indonesia, rather than going unreported, than before.[82] [83] From a United Nations report of Central Coffee, two% of the women (age xv-49) were victims of domestic abuse inside the previous 12-month period. eleven% of the women had been subject to domestic violence during some menses of their life.[72] |

| Iraq | Another study had done a cantankerous sectional exam between 2 different groups. Group ane (G1) representing Christian civilization in the Ankawa district, then group 2 (G2) representing Muslim culture in the Erbil city distrcit. The overall results had stated that overall level of violence (physical and or sexual) was two% higher in Group 2(twenty%). In improver to, psychological violence was twoscore% in group 2 whereas compared group i it was only 24%.[84] Although these factors may indicate that islam may be the crusade of the violence, it has been reported that factors that gave major influence were alcoholic husbands and the wives having to do manual work, compared to professionals in the surface area of Erbil for group 2.[85] |

| Iran | In Iran the nature of domestic violence is complicated by both a national culture and authoritative state that support command, oppression and violence against women.[86] A World Health Arrangement (WHO) study in Babol found that within the previous yr fifteen.0% of wives had been physically driveling, 42.4% had been sexually driveling and 81.5% had been psychologically abused (to various degrees) by their husbands, blaming low income, young age, unemployment and depression educational activity.[87] In 2004 a study of domestic violence was undertaken by the Women'south Center for Presidential Advisory, Ministry building of Higher Education and The Interior Ministry of capital cities in Iran's 28 provinces. 66% married women in Iran are subjected to some kind of domestic violence in the first yr of their marriage, either by their husbands or past their in-laws. All married women who were participants in this written report in Iran have experienced 7.four% of the ix categories of abuse. The likelihood of being subject to violence varied: The more children in a family or the more rural the family lived, the greater the likelihood of domestic violence; Educated and career women were less probable to be victims of abuse. 9.63% of women in the study reported wishing their husbands would die, equally a result of the abuse they have experienced.[86] |

| Jordan | The 2012 United Nations Women's study found that at least one in v women in Jordan has experienced concrete domestic violence in her lifetime, while 1 in seven reports having experienced domestic physical violence in concluding 12 months.[76] Islamic scholars[89] claim mundane domestic violence such as slapping and battering by husband orfamily members is hugely unreported in Jordan, along with other Middle Eastern countries. |

| Morocco | In Morocco, the well-nigh common reason women seek to terminate a union is to extricate themselves from a situation in which they are vulnerable to domestic violence, equally 28,000 acts of domestic violence was reported between 1984 and 1998.[90] |

| Pakistan | A 2011 report claims eighty% of women in Pakistan suffer from domestic abuse.[91] A 2004 study claimed 50% of the women in Islamic republic of pakistan are physically battered and ninety% are mentally and verbally abused by their men,[92] while other reports merits domestic violence rates between 70% to over 95% in Pakistan.[93] [94] Before studies from 1970s to 1990s suggest similar incidence rates of domestic violence in Islamic republic of pakistan.[95] [96] [97] In Pakistan, domestic violence occurs in forms of beatings, sexual violence, torture, mutilation, acid attacks and burning the victim alive (helpmate burning).[98] According to the Islamic republic of pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences in 2002, over xc% of married Pakistani women surveyed reported being kicked, slapped, beaten or sexually abused by their husbands and in-laws.[99] Over 90% of Pakistani women consider domestic violence as a norm of every woman'southward married life.[100] Between 1998 and 2003 at that place were more 2,666 women killed in award killings by a family member.[72] The Thomson Reuters Foundation has ranked Pakistan third on the list of most unsafe countries for women in the world.[101] |

| Gaza Strip | In ane study, half of 120 women interviewed in the Gaza Strip had been the victims of domestic violence.[102] |

| Saudi Arabia | Saudi arabia's National Family Protection Programme estimates that 35 percent of Saudi women take experienced violence.[103] In some recent high-profile cases such as that of Rania al-Baz, Muslim women have publicized their mistreatment at the hands of their husbands, in hopes that public condemnation of wife-beating will finish toleration of the practice.[104] |

| Syria | Ane recent study, in Syria, plant that 25% of the married women surveyed said that they had been browbeaten by their husbands.[105] Some other study establish that 21.8% of women accept experienced some class of domestic violence; 48% of the women who experienced some grade of violence had been browbeaten.[72] |

| Turkey | A 2009 report published past the Government of Turkey reports widespread domestic violence confronting women in Turkey. In urban and rural areas, 40% of Turkish women reported having experienced spousal violence in their lifetime, 10% of all women reported of domestic abuse within last 12 months. In the fifteen-24 yr historic period group, 20% of the women reported of domestic violence by their husbands or male members of their family. The domestic violence ranged from slapping, battering and other forms of violence. The injuries, as a effect of the reported domestic violence included bleeding, broken bones and other forms needing medical attending. Over half reported severe injuries. A third of all women who admitted domestic abuse cases, claimed having suffered repeat domestic corruption injuries in excess of 5 times.[106] Another Un study in E and South-East Anatolia in 1998, 58% of the women (age 14-75) had been bailiwick to domestic violence during some period of their life; some of the women in the sampling had never been in a human relationship which might have otherwise resulted in a college statistic. |

Laws and prosecution

According to Ahmad Shafaat, an Islamic scholar, "If the married man beats a wife without respecting the limits fix downwards past the Qur'an and Hadith, then she can take him to court and if ruled in favor has the right to apply the law of retaliation and beat the husband as he shell her."[twenty] However, laws against domestic violence, as well every bit whether these laws are enforced, vary throughout the Muslim world.

Some women want to fight the abuses they face up as Muslims; these women want "to retain the communal extended family aspects of traditional club, while eliminating its worst abuses, by seeking piece of cake ability to divorce men for corruption and forced marriages."[107]

| Nation | Laws and prosecution |

|---|---|

| People's republic of bangladesh | The Domestic Violence (Protection and Prevention) Act, 2010 was passed on 5 October 2010 to prosecute abusers and provide services to victims. To implement the constabulary, inquiry is needed to identify steps required to back up the law.[74] |

| Egypt | The Egyptian Penal Code was amended to no longer provide impunity (legal protection) to men who married the women that they raped.[72] In 2020, protests have been mounted against Article 237 of the Egyptian Penal Code which allows for a lesser penalisation for men who kill their wives than for other forms of murder.[108] |

| Iran | Existing laws (Iranian Lawmaking of Criminal Procedure manufactures 42, 43, 66) intend to prohibit violence in the form of kidnapping, gender-based harassment, abuse of pregnant women and "crimes against rights and responsibilities inside the family structure," just due to cultural and political culture do not protect women, prosecute their abusers and provide services to victims.[86] [109] The government has laws that support violence confronting women in the case of adultery, including flogging, imprisonment and death.[86] Laws to better enforce existing laws and protect women against violence were placed before the Iranian parliament the week catastrophe xvi September 2011, focusing on both protection and prevention of violence confronting women, including focus on human trafficking, better protection and services for abuse victims, rehabilitation (particularly concerning domestic abuse) and better processes to manage questioning of female offenders. One of the keys to ultimate success is altering customs cultural views regarding the use of violence against women.[109] |

| Morocco | In 1993 as a response to the women's rights activism against aspects of Moroccan family law that are discriminatory or otherwise harmful to women, Male monarch Hassan II had instituted some modest reforms of the Mudawwana, and in 1998, he authorized Prime number Minister El-Yousoufi to propose further changes. When King Hassan II died in 1999, the throne passed to his son, Muhammad VI, who committed to bolder reforms to amend the status of women.[90] Opponents of the program argued that this reform conflicted with women's duties to their husbands and contravene their sharia-based condition as legal minors. Nevertheless, the controversy marked past the huge competing demonstrations intimidated the regime, which led to the withdrawal of the programme. |

| Pakistan | With the exception of Islamabad Upper-case letter Territory,[110] domestic violence is not explicitly prohibited in Pakistani domestic police[111] [112] and most acts of domestic violence are encompassed by the Qisas (retaliation) and Diyat (compensation) Ordinance. Nahida Mahboob Elahi, a human rights lawyer, has said that new laws are needed to better protect women: "At that place needs to be special legislation on domestic violence and in that context they must mention that this is violence and a crime."[97] Police and judges oftentimes tend to care for domestic violence equally a not-justiciable, individual or family affair or, an issue for civil courts, rather than criminal courts.[113] In Pakistan, "police oftentimes refuse to register cases unless there are obvious signs of injury and judges sometimes seem to sympathise with the husbands."[97] In 2008, campaigners said that at a time when violence against women is rampant in Pakistani society this so-called women'south protection neb encourages men to abuse their wives.[61] In 2009, a Domestic Violence Protection bill was proposed by Yasmeen Rehman of the Pakistan People'southward Party. It was passed in the National Associates[114] simply subsequently failed to be passed in the second chamber of parliament, the Senate, within the prescribed flow of time.[115] The Quango of Islamic Ideology objected to the bill, claiming in its current form it would increase divorces and that it ignored adult male victims of domestic violence.[116] Afterwards the passage of Eighteenth ramble amendment, the affair pertaining to the bill became a provincial issue.[117] It was re-tabled in 2012, just met with a deadlock in parliament considering of stiff opposition from the religious correct. Representatives of Islamic organizations vowed resistance to the proposed bill, describing it as "anti-Islamic" and an attempt to promote "Western cultural values" in Pakistan. They asked for the bill to be reviewed earlier being approved by the parliament.[118] The beak was eventually passed for Islamabad Capital Territory on 20 February 2012.[110] [117] [119] [120] |

| Kingdom of saudi arabia | Only in 2004, after international attending was fatigued to the case of Rania al-Baz, was there the first successful prosecution for domestic violence.[121] |

| Turkey | Laurels killings are now punishable by life imprisonment and Turkish police force no longer provides impunity (legal protection) to men who married the women that they raped.[72] |

| Tunisia | In Tunisia, domestic violence is illegal and punishable by five years in prison.[122] |

Victim support programs

In Malaysia, the largest regime-run hospital implemented a programme to intervene in cases where domestic violence seems possible. The woman is brought to a room to meet with a counselor who works with the patient to decide if the adult female is in danger and should be transferred to a shelter for safety. If the adult female does not wish to become to the shelter, she is encouraged to run across a social worker and file a constabulary report. If the injury is very serious, investigations brainstorm immediately.[72] [nb ten]

Divorce

Though some Muslim scholars, such as Ahmad Shafaat, fence that Islam permits women to be divorced in cases of domestic violence.[xx] Divorce may be unavailable to women equally a practical or legal matter.[123]

The Quran states: (2:231) And when you accept divorced women and they have fulfilled the term of their prescribed menstruation, either take them back on reasonable footing or fix them costless on reasonable basis. But do not take them back to injure them, and whoever does that, so he has wronged himself. And treat not the Verses of Allah every bit a jest, but remember Allah's Favours on you, and that which He has sent down to yous of the Volume and Al-Hikmah [the Prophet's Sunnah, legal ways, Islamic jurisprudence] whereby He instructs you. And fear Allah, and know that Allah is All-Enlightened of everything.[124]

Although Islam permits women to divorce for domestic violence, they are subject to the laws of their nation which might brand information technology quite difficult for a woman to obtain a divorce.[iii]

Most women'southward rights activists concede that while divorce can provide potential relief, it does not constitute an acceptable protection or even an option for many women, with discouraging factors such as lack of resources or support to establish alternative domestic arrangements and social expectations and pressures.[125]

Meet also

- AHA Foundation, not-profit for women's rights in western countries

- Dowry expiry

- Female infanticide

- Femicide

- Gender roles in Islam

- Glossary of Islam

- Islamic feminism

- Peaceful Families Project - Muslim organization

- Sharia#Women

- Taliban treatment of women

- Violence against women

- Women and Islam

Other

- International Periodical for the Psychology of Faith

- Outline of domestic violence

- Victimology

- Violence confronting women

- Women'due south rights

References

Citations

- ^ Hajjar, Lisa (2004). "Religion, Country Ability, and Domestic Violence in Muslim Societies: A Framework for Comparative Analysis". Constabulary and Social Inquiry. 29 (1): i–38. doi:x.1111/j.1747-4469.2004.tb00329.x. S2CID 145681085.

- ^ "Domestic Violence". Merriam Webster . Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ a b "Farther Promotion and Encouragement of Human being Rights and Fundamental Freedoms". United nations Economic and Social Council. 5 February 1996. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ General Associates (20 Dec 1993). 85th plenary session: announcement on the elimination of violence against women. United nations. A/RES/48/104. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ Shahroodi, Yard., Besharati, Z. (2020). 'Reciting of Women Beating in An-nisa' verse :34', Jurisprudence the Essentials of the Islamic Law, 53(1), pp. 125-144. doi: 10.22059/jjfil.2020.311500.669026

- ^ "Quran four:34". Islam Awakened . Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Hajjar, Lisa (2004). "Faith, country ability, and domestic violence in Muslim societies: A framework for comparative assay". Law & Social Inquiry. 29 (1): i–38. doi:ten.1111/j.1747-4469.2004.tb00329.ten. S2CID 145681085.

- ^ Treacher, Amal. "Reading the Other Women, Feminism, and Islam." Studies in Gender and Sexuality 4.1 (2003); pages 59-71

- ^ John C. Raines & Daniel C. Maguire (Ed), Farid Esack, What Men Owe to Women: Men'due south Voices from Globe Religions, Country University of New York (2001), see pages 201-203

- ^ Jackson, Nicky Ali, ed. Encyclopedia of domestic violence. CRC Press, 2007. (see chapter on Qur'anic perspectives on wife abuse)

- ^ Ahmed, Ali S. V.; Jibouri, Yasin T. (2004). The Koran: Translation. Elmhurst, NY: Tahrike Tarsile Qurʼān. Print.

- ^ a b "1000 Ayatullah Nasir Makarem Shirazi: Fatwas and viewpoints". Al-Ijtihaad Foundation . Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Roald, Anne South. (2001). Women in Islam: The Western Experience. Routledge. ISBN 0415248965. p 166

- ^ a b Ali, Abdullah Yusuf, (1989) The Holy Qur'an: Text, Translation and Commentary. Brentwood, MD: Amana Corporation. ISBN 0-915957-03-5.

- ^ Yusuf al-Qaradawi (2013). The Lawful and the Prohibited in Islam. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Book Trust. p. 227. ISBN978-967-0526-00-three.

- ^ Ibn Kathir, "Tafsir of Ibn Kathir", Al-Firdous Ltd., London, 2000, 50-53

- ^ "Tafseer al-Tabari for iv:34".

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Muhsin; Hilālī, Taqī Al-Dīn. (1993) Interpretation of the Meanings of the Noble Qur'an in the English language Language: a Summarized Version of At-Tabari, Al-Qurtubi and Ibn Kathir with Comments from Sahih Al-Bukhari. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Maktaba Dar-us-Salam. Impress.

- ^ Archetype Manual of Islamic Sacred Police, Al-Nawawi, section m10.12, "Dealing with a Rebellious Married woman", page 540; may striking her every bit long as it doesn't draw blood, leave a bruise, or break bones.

- ^ a b c Shafaat, Ahmad (2000) [1984]. "Tafseer of Surah an-Nisa, Ayah 34". Archived from the original on March 27, 2002. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Muhammad Asad, The Message of the Qur'an (his translation of the Qur'an).

- ^ Badawi, Jamal. "Is married woman beating allowed in Islam?". The Mod Organized religion.

- ^ Kathir, Ibn, "Tafsir of Ibn Kathir", Al-Firdous Ltd., London, 2000, 50-53.

- ^ a b Roald, Anne S. (2001). Women in Islam: The Western Experience. Routledge. ISBN 0415248965. p. 169

- ^ "Quran Surah An-Nisaa (Verse 34) with English language Translation الرِّجَالُ قَوَّامُونَ عَلَى النِّسَاءِ بِمَا فَضَّلَ اللَّهُ بَعْضَهُمْ عَلَىٰ بَعْضٍ وَبِمَا أَنْفَقُوا مِنْ أَمْوَالِهِمْ ۚ فَالصَّالِحَاتُ قَانِتَاتٌ حَافِظَاتٌ لِلْغَيْبِ بِمَا حَفِظَ اللَّهُ ۚ وَاللَّاتِي تَخَافُونَ نُشُوزَهُنَّ فَعِظُوهُنَّ وَاهْجُرُوهُنَّ فِي الْمَضَاجِعِ وَاضْرِبُوهُنَّ ۖ فَإِنْ أَطَعْنَكُمْ فَلَا تَبْغُوا عَلَيْهِنَّ سَبِيلًا ۗ إِنَّ اللَّهَ كَانَ عَلِيًّا كَبِيرًا". IReBD.com.

- ^ Ali, Ahmed. "34 القرآن, النساء". Tanzil.cyberspace (in Urdu). p. 84.

مرد عورتوں پر حاکم ہیں اس واسطے کہ الله نے ایک کو ایک پر فضیلت دی ہے اور اس واسطے کہ انہوں نے اپنے مال خرچ کیے ہیں پھر جو عورتیں نیک ہیں وہ تابعدار ہیں مردوں کے پیٹھ پیچھے الله کی نگرانی میں (ان کے حقوق کی) حفاظت کرتی ہیں اور جن عورتو ں سےتمہیں سرکشی کا خطرہ ہو تو انہیں سمجھاؤ اور سونے میں جدا کر دو اور مارو پھر اگر تمہارا کہا مان جائیں تو ان پر الزام لگانے کے لیے بہانے مت تلاش کرو بے شک الله سب سے اوپر بڑا ہے (34)

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil (March 25, 2007). "Verse in Koran on beating wife gets a new translation". The New York Times . Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "Wife Beating is not allowed in Islam in any case!". Islamawareness.net . Retrieved May v, 2021.

- ^ William Lane, Edward. "Arabic-English Lexicon by Edward William Lane (London: Willams & Norgate 1863)". pp. 1777–1783. Archived from the original on 2015-04-08.

- ^ Shahroodi, M., Besharati, Z. (2020). 'Reciting of Women Beating in An-nisa' verse :34', Jurisprudence the Essentials of the Islamic Law, 53(1), pp. 125-144. doi: 10.22059/jjfil.2020.311500.669026

- ^ a b c d "Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition: Volume Review". Journal of Islamic Ideals. 1 ((1-two)): 203–207. 2017. doi:10.1163/24685542-12340009.

- ^ Ayesha S. Chaudhry (20 December 2013). Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition. OUP Oxford. pp. 103–. ISBN978-0-19-166989-7.

- ^ Ayesha Southward. Chaudhry (20 December 2013). Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition. OUP Oxford. pp. 104–. ISBN978-0-xix-166989-7.

- ^ a b c Ayesha S. Chaudhry (20 December 2013). Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition. OUP Oxford. pp. 105–. ISBN978-0-xix-166989-vii.

- ^ Ayesha South. Chaudhry (20 Dec 2013). Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition. OUP Oxford. pp. 106–. ISBN978-0-xix-166989-7.

- ^ Ayesha South. Chaudhry (20 Dec 2013). Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition. OUP Oxford. pp. 107–. ISBN978-0-xix-166989-7.

- ^ a b Ayesha S. Chaudhry (20 Dec 2013). Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition. OUP Oxford. pp. 108–. ISBN978-0-nineteen-166989-7.

- ^ John R. Bowen (15 March 2016). On British Islam: Religion, Law, and Everyday Practice in Shariʿa Councils. Princeton University Press. pp. 49–. ISBN978-0-691-15854-9.

- ^ Masud, Muhammad Khalid (2019). "Modernizing Islamic Law in Islamic republic of pakistan: Reform or Reconstruction?". Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. 42 (2): 78. doi:10.1353/jsa.2019.0006. S2CID 239219154.

- ^ a b Ayesha S. Chaudhry (xx Dec 2013). Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition. OUP Oxford. pp. 121–122. ISBN978-0-19-166989-vii.

- ^ Jonathan A.C. Chocolate-brown, Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet'southward Legacy, Oneworld Publications (2014), pp. 275-276

- ^ Muhammad al-Bukhari. "Wedlock, Marriage (Nikaah)". Sunnah.com . Retrieved ix March 2020.

- ^ a b Idriss, Mohammad Mazher; Abbas, Tahir. (2011) "Honour, Violence, Women and Islam." Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. Print.

- ^ Chaudhry, Muhammad Sharif. Prophet Muhammad: equally Described in the Holy Scriptures. Lahore: Due south.N. Foundation, 2007. Print.

- ^ "Pct of women aged 15–49 who remember that a hubby/partner is justified in hitting or beating his married woman/partner under certain circumstances". Childinfo. January 2013. Archived from the original on July 4, 2014. Retrieved May five, 2021.

- ^ a b "Towards Understanding the Qur'an" Translation by Zafar I. Ansari from "Tafheem Al-Qur'an" by Syed Abul-A'ala Mawdudi, Islamic Foundation, Leicester, England. Passage was quoted from commentary on 4:34.

- ^ Suad Joseph, Afsaneh Najmabadi (ed.). Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 122. ISBN9004128190.

- ^ "Sunan Abi Dawud, Book xi, Hadith 2138".

- ^ "Does Islam Permit Wife-Beating?, Islam, Women and Feminism, Aiman Reyaz, New Age Islam, New Historic period Islam". newageislam.com. Archived from the original on 2019-eleven-25. Retrieved 2020-01-27 .

- ^ "Sunan Abi Dawud, Book 11, Hadith 2139". Retrieved i September 2015.

- ^ Al-Baghawi. "Mishkat Al-Masabih". 2: 691.

- ^ "Sunan Abi Dawud, Book eleven, Hadith 2137". Sunnah.com.

- ^ Ibn Kathir 1981 vol I: 386, Sunan Abi Dawud, Book of Marriage #1834, ad-Darimi, Book of Marriage #2122; quoted in Roald (2001) p. 167

- ^ Constable, Pamela (May 8, 2007). "For Some Muslim Wives, Abuse Knows No Borders". Washington Mail service . Retrieved May five, 2021.

- ^ Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn; Bardsley-Sirois, Lois (1990). "Obedience (Ta'a) in Muslim Union: Religious Estimation and Practical Law in Egypt". Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 21 (1): 39–53. doi:x.3138/jcfs.21.1.39.

- ^ Maghraoui, Abdeslam (2001). "Political authority in crisis: Mohammed Half dozen'due south Morocco". Middle East Report. 218 (218): 12–17. doi:10.2307/1559304. JSTOR 1559304.

- ^ Critelli, Filomena M. "Women's rights= Human rights: Pakistani women against gender violence." J. Soc. & Soc. Welfare 2010; 37, pages 135-142

- ^ Oweis, Arwa; et al. (2009). "Violence Against Women Unveiling the Suffering of Women with a Low Income in Jordan". Journal of Transcultural Nursing. twenty (ane): 69–76. doi:10.1177/1043659608325848. PMID 18832763. S2CID 21361924.

- ^ "UAE: Spousal Abuse Never a 'Right' - Man Rights Watch". hrw.org. 19 Oct 2010.

- ^ "CII recommends 'lite beating' for married woman if she defies married man". Duyan News. 26 May 2016. Retrieved May v, 2021.

- ^ a b Dackevych, Alex (16 June 2008). "Mullah defends 'crush your wives lightly' advice". BBC . Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "IRIN Middle E - Lebanon: Move to take domestic violence cases out of religious courts - Lebanon - Gender Issues - Governance - Human Rights". IRINnews. 23 September 2009.

- ^ "Lebanese republic: Enact Family Violence Bill to Protect Women - Human Rights Watch". hrw.org. 6 July 2011.

- ^ Moha Ennaji and Fatima Sadiq, Gender and Violence in the Middle E, Routledge (2011), ISBN 978-0-415-59411-0; see pages 162-247

- ^ "Saudi arabia cabinet approves domestic abuse ban". BBC NEWS. 28 August 2013.

- ^ Taylor, Pamela Grand. (27 February 2009). "Aasiya Zubair Hassan, Domestic Violence and Islam - Pamela K. Taylor". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 3, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan - Ending Kid Marriage and Domestic Violence" (PDF). Human Rights Picket. 2009. pp. eleven–13. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Ward, Olivia (March viii, 2008). "Ten Worst Countries for Women". Toronto Star . Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Bohn, Lauren (8 December 2018). "'We're All Handcuffed in This State.' Why Afghanistan Is Still the Worst Identify in the World to Be a Woman". Time . Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Violence confronting women". World Health Organization. March 9, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence confronting Women". Earth Health Organization. Archived from the original on January 13, 2006. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i "In-depth study on all forms of violence against women". UN Women . Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Naved, Ruchira Tabassum; Persson, Lars. (2005) "Factors Associated with Spousal Physical Violence Against Women in Bangladesh." Studies in Family Planning 36.4 Pages 289-300.

- ^ a b "From research to legislation: ICDDR,B celebrates the passing of the Domestic Violence Act in People's republic of bangladesh". icddr,b. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^

- ^ a b "Progress of the World'due south Women 2015-2016" (PDF). My Favorite News. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-07.

- ^ "The Condition and Progress of Women in Centre Eastward and North Africa, Washington DC" (PDF). siteresources.worldbank.org. World Depository financial institution Social Development Group. 2010.

- ^ Sudha Sharma (21 March 2016). The Status of Muslim Women in Medieval India. SAGE Publications. pp. 51–. ISBN978-93-5150-565-5.

- ^ Yasmin, Angbin (2014). "Middle Class Women in Mughal India". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 75: 296–297.

- ^ Yasmin, Angbin (2014). "Middle Class Women in Mughal India". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 75: 296.

- ^ Moosvi, Shireen (1991). "Travails of a Mercantile Community - Aspects of Social Life at the Port of Surat (Earlier Half of the 17th Century)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 52: 402.

- ^ "Gender-based violence in Indonesia, United nations WHO" (PDF). searo.who.int. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2014.

- ^ Un High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld - Republic of indonesia: Protection, services and legal recourse available to women who are victims of domestic violence (2005-2006)". Refworld.

- ^ Al-Tawil N. M. (2012). Association of violence confronting women with organized religion and culture in Erbil Iraq: a cross-sectional written report. BMC public health, 12, 800. https://doi.org/x.1186/1471-2458-12-800

- ^ Al-Tawil N. G. (2012). Association of violence against women with religion and civilisation in Erbil Republic of iraq: a cantankerous-sectional study. BMC public health, 12, 800. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-800

- ^ a b c d Moradian, Azad (August 2009). "Domestic Violence against Single and Married Women in Iranian Society". Tolerancy International. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved May v, 2021.

- ^ Faramarzi, M.; Esmailzadeh, S.; Mosavi, Due south. (2005). "Prevalence and determinants of intimate partner violence in Babol city, Islamic Republic of Iran" (PDF). Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. Earth Health Organization. 11 (half-dozen): 870–879. PMID 16761656. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Esfandiari, Golnaz (February 8, 2006). "Islamic republic of iran: Self-Immolation Of Kurdish Women Brings Concern". Radio Gratis Europe . Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Zahia Salh (2013), Gender and Violence in Islamic Societies: Patriarchy, Islamism and Politics in the Middle Eastward and North Africa (Library of Modernistic Middle Due east Studies), Tauris, ISBN 978-1780765303; see page twoscore

- ^ a b Euben, Roxanne Leslie; Zaman, Muhammad Qasim. (2009) Princeton Readings in Islamist Thought: Texts and Contexts from Al-Banna to Bin Laden. Princeton University Printing. ISBN 9780691135885.

- ^ "4 in v women in Islamic republic of pakistan face up some form of domestic corruption: Study". The Tribune. March 2, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Niaz, U (2004). "Women's mental wellness in Islamic republic of pakistan". World Psychiatry. three (ane): threescore–2. PMC1414670. PMID 16633458.

- ^ T. Southward. Ali; I. Bustamante-Govino (2007). "Prevalence of and reasons for domestic violence among women from depression socioeconomic communities of Karachi" (PDF). Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 13 (half-dozen): 1417–1421. doi:10.26719/2007.13.6.1417. PMID 18341191. Retrieved May five, 2021.

- ^ Ireland, Corydon (April 28, 2010). "Horror, by custom". Harvard Gazette . Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Ministry building of Women's Evolution (1987), "Dilapidated Housewives in Islamic republic of pakistan", Islamabad

- ^ State of Human Rights in 1996, Man Rights Commission of Pakistan. p. 130;

- ^ a b c Price, Susanna (August 24, 2001). "Pakistan's rising toll of domestic violence". BBC News . Retrieved May five, 2021.

- ^ "Women's Rights - Our Struggle to fight for the rights of women". Ansar Burney Trust. Archived from the original on 2007-01-14. Retrieved 2006-12-29 .

- ^ "Pakistan: Violence confronting women: Media briefing". Amnesty International . Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "Domestic violence owned, but awareness slowly rising". The New Humanitarian. March 11, 2008. Retrieved May five, 2021.

- ^ Mahwish, Qayyum (6 July 2017). "Domestic violence victims left on their ain in Islamic republic of pakistan". New Internationalist . Retrieved nine March 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Doug (June 23, 2000). "Addressing Violence Against Palestinian Women". IDRC. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia: 10 Reasons Why Women Abscond". Human Rights Watch. 10 January 2019. Retrieved May v, 2021.

- ^ Al-Jadda, Souheila (May 12, 2004). "Saudi TV host'due south beating raises taboo topic: domestic violence against Muslim women". Christian Science Monitor . Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Zoepf, Katherine (April 11, 2006). "U.Northward. Finds That 25% of Married Syrian Women Have Been Beaten". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved May v, 2021.

- ^ "Domestic violence against women in Turkey" (PDF). Elma Teknik Basim Matbaacilik. 2009.

- ^ Ask, Karin; Marit Tjomsland. (1998) Women and Islamization: gimmicky dimensions of discourse on gender relations. Oxford: Berg. Folio 47. ISBN 185973250X.

- ^ "Catastrophe Sex Discrimination in the Constabulary - "Honor" Killings" (PDF). Equality At present. p. 51. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Iran enforces laws on prevention of violence confronting women: Iranian MP". High Quango For Human Rights. xvi September 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Wasim, Amir (Feb 21, 2012). "Domestic violence no more than a individual matter". Dawn.

- ^ Bettencourt, Alice (2000). "Violence against women in Pakistan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February five, 2005. Retrieved May five, 2021.

- ^ Rehman, I.A. (1998). The Legal rights of women in Islamic republic of pakistan, theory & practice. Page ix, 1998.

- ^ Yasmine Hassan, The Haven Becomes Hell, (Lahore: Shirkat Gah, 1995), pp. 57, 60.

- ^ Ghauri, Irfan (August 5, 2009). "NA passes law confronting domestic violence". Daily Times.

- ^ Zahid Gishkori (half dozen April 2012). "Opposition forces regime to defer women domestic violence bill". The Limited Tribune . Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ Nasir Iqbal (24 August 2009). "Domestic Violence Nib to push upwardly divorce rate: CII". Dawn . Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ a b Ayesha Shahid (vii Apr 2012). "Domestic violence bill gets new expect". Dawn . Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Gishkori, Zahid (April 17, 2012). "Citing 'controversial' clauses: Clerics vow to resist passage of Domestic Violence Beak". The Express Tribune.

- ^ "Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Human activity, 2012" (PDF). Senate of Pakistan. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ "Domestic Violence (Prevention & Protection) Act 2012" (PDF). Aurat Publication & Information Service Foundation . Retrieved three Apr 2015.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia". Amnesty International. 2005. Archived from the original on January 12, 2006. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Sterett, Brittany (June ten, 2005). "Tunisia Praised for Efforts To Protect Women's Rights". Archived from the original on June xiv, 2007. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Gavin. "Marriage and Divorce in Islamic Due south East Asia."

- ^ Muḥammad, Farida Khanam; Ḫān, Wahīd-ad-Dīn. (2009). The Quran. New Delhi: Goodword. Impress.

- ^ Adelman, Howard, and Astri Suhrke. (1999). The Path of a Genocide: the Rwanda Crisis from Uganda to Zaire. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. ISBN 0765807688.

Notes

- ^ Abdullah Yusuf Ali in his Quranic commentary states that: "In instance of family jars 4 steps are mentioned, to exist taken in that guild. (1) Peradventure verbal communication or admonition may exist sufficient; (two) if not, sexual practice relations may be suspended; (3) if this is not sufficient, some slight physical correction may be administered; but Imam Shafi'i considers this inadvisable, though permissible, and all authorities are unanimous in deprecating whatsoever sort of cruelty, even of the nagging kind, as mentioned in the next clause; (4) if all this fails, a family council is recommended in passage iv:35."[14]

- ^ Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, caput of the European Council for Fatwa and Research, says that "If the husband senses that feelings of defiance and rebelliousness are rising confronting him in his wife, he should endeavor his best to rectify her attitude by kind words, gentle persuasion, and reasoning with her. If this is not helpful, he should sleep autonomously from her, trying to awaken her agreeable feminine nature and so that serenity may be restored, and she may respond to him in a harmonious manner. If this approach fails, it is permissible for him to trounce her lightly with his hands, avoiding her face and other sensitive parts."[fifteen]

- ^ Ibn Kathir Advertising-Damishqee records in his Tafsir Al-Qur'an Al-Azim that "Ibn `Abbas and several others said that the Ayah refers to a beating that is not tearing. Al-Hasan Al-Basri said that it means, a beating that is non severe."[twenty]

- ^ Ane such authority is the earliest hafiz, Ibn Abbas.[22]

- ^ Muhammad is attributed to say in the Good day Sermon: "And if they commit open sexual misconduct you lot take the correct to leave them alone in their beds and [if even so, they exercise not listen] trounce them such that this should not go out any marking on them." Sunan Ibn Maja 1841.

- ^ Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi comments that "Whenever the Prophet permitted a man to administrate corporal punishment to his married woman, he did so with reluctance, and connected to limited his distaste for information technology. And even in cases where it is necessary, the Prophet directed men not to hit across the face, nor to shell severely nor to use anything that might leave marks on the body." "Towards Understanding the Qur'an" Translation by Zafar I. Ansari from "Tafheem Al-Qur'an" (specifically, commentary on 4:34) by Syed Abul-A'ala Mawdudi, Islamic Foundation, Leicester, England.

- ^ The medieval jurist ash-Shafi'i, founder of one of the main schools of Sunni fiqh, commented on this verse that "hit is permitted, only non striking is preferable."

- ^ "[Southward]ome of the greatest Muslim scholars (e.thou., Ash-Shafi'i) are of the opinion that it is but barely permissible, and should preferably be avoided: and they justify this opinion past the Prophet's personal feelings with regard to this problem." Muhammad Asad, The Bulletin of the Qur'an (his translation of the Qur'an).

- ^ India and U.s. were besides noted every bit countries with a high prevalence of decease during pregnancy due to domestic abuse.

- ^ The model for assessing patient safety and providing shelter, social worker and investigative support is existence implemented in other Asian countries and in South Africa.

Further reading

- 'In the Book We Have Left Out Nothing': The Ethical Problem of the Existence of Verse 4:34 in the Qur'an" by Laury Silvers

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islam_and_domestic_violence

0 Response to "Everything You Wanted to Know About Severely Whipping and "Beating" Your Sex Partner"

Post a Comment